2. Court decisions are not evidence-based

Children in youth care hardly ever get examined by a registered psychologist or psychiatrist. Most of the time assessments are made by a less qualified behavioural ‘experts’ who are not academically qualified at all. And certainly they are not independent, but come either from within Jeugdzorg’s own organisation, or from an external institution with close ties to Jeugdzorg. Yet these non-qualified opinions are routinely submitted to Dutch court as being equivalent to “expert evidence”.

Also the Dutch law in CPS matters is very vague. Just a small section of a page in the civil code (Burgerlijk wetboek, Art. 255: https://maxius.nl/burgerlijk-wetboek-boek-1/artikel255/lid1) describes in very general terms if or when a child is in serious danger. Judges have no precise legislative tools to check if the social workers are telling the truth, if they have done their job properly and if the danger for the child is really clear and present.

3. The judicial system is heavily biased towards child removal

Judge’s fear makes them heavily biased to remove children because of the very few exceptions where children did lose their lives, (very often under guidance of the CPS workers!) this made big headlines in the newspapers. Judges have little time for dossiers which are frequently over a thousand pages. So they usually choose to rely upon the statements made by the social workers.

4. False evidence is permitted to pile up on false evidence

The judge is in most cases not at all convinced the social workers have done a proper job or even speak the truth, but just orders for ‘more investigation’. The investigations themselves however, that are usually deliberately stretched over a long period of time, are a perfect opportunity for youth care and the Board of Child Protection (RvdK) to find, signal or suspect more ‘alarming signals’.

When a child was illegally taken from the parents, the tendency is in a later stage to present the judge with completely different ‘worries’ and accusations towards the parents, then at the beginning of the whole process. The initial (illegal) reason for taking the child away slowly disappears under the surface under the weight of the new false evidence. After several court meetings the dossiers become too thick and too complicated to trace everything back to the beginning.

Judges base their ruling most of the time on the most recent developments in a case, meaning that if a child is already under state supervision, all the recent (frequently false) observations made by the social workers will count and injustice right from the start is forgotten about.

5. Youth care professionals cover up each other’s mistakes

Many youth care cases are built upon nothing more than a long list of subjective suspicions, opinions and impressions. Often times it becomes more of a power struggle between parents and social workers then a search for truth or good care taking of the child’s needs. Parents are always in the disadvantage because they are up against a whole range of persons and organisations who close their ranks and align their goals behind closed doors.

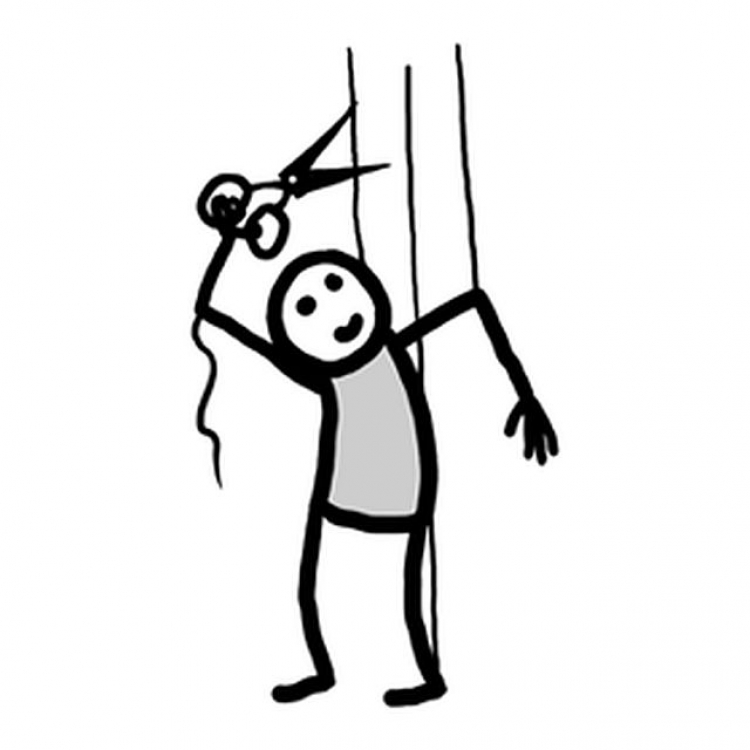

A Dutch critic of the youth care system (Harry Berndsen) has called this the “Stupidity-Chain”. All the organisations involved duplicate each other’s false evidence and wrong assumptions, thus during the process of so called ‘investigation’ the number of accusers will rise, but based upon the same false

information. There is no fact checking performed that could break the whole chain.

In a system based upon ‘professional’ opinions, parents usually lose by numbers. All the professionals - who are closely connected by numerous cases over the years - will cover for each other and no mistake will be corrected or even come to the surface. If parents respond with evidence proving the social workers are wrong or even deliberately lying, the social workers will respond with being sorry the parents ‘feel this way’. As if the parents are not stating facts, but are merely expressing emotions.

It is very hard, not to say impossible to make a case against social workers because in civil court they cannot be accused of perjury. They are not under oath and there is no government control over their activities.

6. No fact checking ever occurs after children are removed from home

Parents cannot prove their innocence because the civil court is not based upon objective evidence, but upon subjective opinions, impressions and suspicions of social workers. Innocence is virtually impossible since facts don’t matter.

The Board of Child Protection theoretically should supervise Youth Care but in reality simply duplicates the majority of their information in their own documents. They virtually never correct mistakes raised by parents or third parties within Youth Care dossiers. They act as virtually the same organization.

The Netherlands Youth Institute report of 2011 (http://www.nji.nl/nl/Download-NJi/Publicatie-NJi/Beter_beslissen_over_Kindermishandeling.pdf) on “Research into the effects of structured judgment through ORBA [child protection decision-making]” states that it did not investigate the ability of social workers to determine if a child was truly abused or not. This is very typical for the Dutch youth care: everything is instrumental and about procedures, without asking the question if interventions were actually proven to be necessary in the first place.

At a meeting with politicians, parents and youth care workers in The Hague on 17 February 2010 the then chairperson of the association of child judges (Jolande Calkoen) stated this about the “indication decision” – the document which should answer the of whether the "serious threat" is merely an allegation or a fact:

“I think the [indication decision] is one of the most underexposed and undervalued aspects of the entire youth care. It is messy, it is late and the quality, transparency and substantiation are often very unsound.”

The retired lawyer Peter Prinsen also states this in 2017 (http://svensnijer-essays.blogspot.com/2017/10/peter-prinsen-over-jeugdzorg-deel-3.html )

“The emergency child removal order is a traumatic form of deprivation of liberty for children… The two legal clauses [concerning supervision order and child removal order] stand out due to their meaninglessness. It's just an opinion.

There is no defence against an opinion. The bottom line is that the Child Protection Council and the Jeugdzorg case manager have a blank power of attorney to deprive children of their freedom. There is no review. The law does not provide any legal protection here.”

Also there is no independent investigative judge, as has been proposed by several Dutch lawyers. There is no legality test for judges to check if a child is taken away from its parents or on what grounds it should return home. Investigations into the safety of the child last forever and usually are a cover-up to keep the child in the system even when it was wrongfully taken (and the vast majority of the currently 51,000 removed children were taken without sound evidence of either abuse or neglect).

7. Youth Care and Child protection are not separate systems

When parents seek help for their child via channels of Youth Care they are always at high risk of being accused of child abuse. It works completely different when parents go to their own doctor to get a referral for a psychologist, where clinical help from an academically trained person is risk free. In Youth Care a lot of parents are lured in with promises of help for their child but end up in court being accused of child abuse, either physically, emotionally or mentally.

The reason for this is that in Youth Care the standard assumption is that any problems with the child(ren) are almost always connected to the poor social situation or poor social/parental skills of the parents. A lot of completely normal families end up in this trap. They expect to get help for their child, with learning disability or difficulties with concentration or behaviour, but are shocked to discover that they are the prime ‘suspect’. In a clinical situation first of all the child is examined, but in Youth Care the parents are usually suspected of doing ‘something wrong’ that caused the deviant behaviour of the child. If parents are not well educated and have a tendency to cooperate with the system, nothing more may happen, but if parents have some sort of self-consciousness and dare to question the assumptions of the social workers who do not investigate at a clinical level, things can get ugly very fast.

When the authority of the social workers is questioned, they can become hostile and threaten with legal actions against the parents. The social workers know the system and understand, unlike the parents, how much their professional opinions count in civil court, where hard evidence almost never plays a key role. Putting the opinions, impressions, observations and interpretations of the social workers

into question, is in itself regarded as a ‘sign’ of disobedience and therefore as a signal of child abuse. The logic of the social workers is: if the parents want the best for their child, they will never disobey the social workers, or else something is psychologically or socially wrong with the parents and they are a danger to the child. Of course the better educated parents will resist this system more than average parents, and therefore they are treated relatively harsher by the system. Although the injustice happens on all levels with all sorts of parents.

8. Dutch CPS is a one-way trap with rarely any intention to return removed children

There are two ways of getting into the Dutch CPS trap: either by seeking help for the child voluntarily, or being reported by an (anonymous) person or institution who have ‘concerns’ about the child’s wellbeing. In either case it is highly dependent on the youth care (case manager) and the personal ‘chemistry’ between this person and the parents, what the outcome will be. The truth is rarely the most important matter, because a good relationship with the social worker (cooperation/obedience) is number one.

Most parents who feel that the truth is not being investigated or who expect their child to get a more professional diagnosis by an independent and academically trained person, get into conflict with the system and in most cases will lose control and custody of their child, after a series of court meetings.

Many case managers ignore their legal duty to create a return plan for children to their families once all ‘problems’ are solved (or if no problems are discovered).

9. Dutch CPS failings applied to the specific case of Martin den Hertog

The judge has not determined that the child is in danger and yet still ordered the out-of-home placement. Certainly for an emergency removal order as with Martin, expert medical or psychological confirmation of danger was needed, but this has never been established. The judge bases their decision only on the preliminary ‘suspicions’ of danger put forward by the social workers. The judge has not identified any hazard themself, but orders a follow-up investigation that post-hoc investigation should not take longer than two weeks in the event of serious danger. In practice, the research took more than a year (15 months) for Martin’s psychological screening results to be released (where no abuse or neglect was found). Social workers could have confirmed or disproved from the first contact whether Martin was abused by his parents or whether he simply had autism. But such an assessment never occurred, the child was simply removed instead without being sure of the reasons why.

The judge has not determined whether there is any danger. The judge does not test, they have blindly followed the Social Workers.

Youth care realized afterwards that they made a mistake. Yet they deliberately performed very slow research – which completely exonerated the parents yet even then the child was still not returned. Youth care is angry that Martin's parents brought in the media and have now turned the case into an exercise in revenge.